The Time I Outed Someone to Herself

Trans people often say something along the lines of “If only I could have dealt with this sooner, I was such an idiot!”, but can that process of self discovery be hurried along? Some people advise against trying to help someone along in such deeply personal matters, for example, the Straight Person’s Guide to Gay Etiquette says:

First Rule: Never out someone to him/herself.You may not think this is possible, but it is. Many persons walk about daily giving off more queer vibes than an entire roomful of RuPaul clones, and yet continue to identify as heterosexual. This is because the human capacity for denial and rationalization is unmatched by any other mental phenomenon in the known universe. Ask Spock if you don’t believe me. Your pal Bill may have just spent half an hour talking about how beautiful Jaye Davidson is and how he watched Stargate on slow motion, he may have pierced ears, tattoos, graceful and fluttering hand gestures and a fondness for hot dogs that you are sure has to be Freudian, he may just have ended his third brief and unhappy marriage, but if you sit Bill down and say, “Three strikes and you’re out, Bill, I think you need to start looking for love in quite different places,” he will be shocked, appalled, horrified, and more than a little angry. If Bill were ready or able to confront this possibility, it would have happened by now, and your well-meaning intervention will only alienate him and perhaps drive him further into the depths of repression. You must wait for Bill to get his own clue. And when he does come out to you, don’t forget to feign surprise.

This might be reasonable advice for clueless straight people dealing with potentially gay-but-in-denial people. It’s hard to imagine Bill saying “Duh, I guess I should date men!” in response to the clumsy approach above. But it would be ridiculous to think that no one can ever help another person gain some perspective in their process of self discovery; after all, that’s pretty much the raison d’être for therapy (and friendship too)—nonjudgmental questions from someone else can help someone in drawing meaningful and useful conclusions about their lives.

Context matters, too. Would we have the same advice in the (mythical) Gay Person’s Guide to Gay Etiquette? Suppose, for example, we switch the scenario around and have Bill waking up next to Paul after a night of passionate sex. If Bill says to Paul, “I’m not doing anything gay because you went down on me and I was never penetrated! And anyway, it’s just sex, it doesn’t mean anything!” maybe it’s okay for Paul to say, “WTF!? Do you think that if anyone opened the door on us while we were fucking, they’d make the distinction? Most ‘totally straight’ guys don’t screw dudes the moment their wives go out of town. And if you think it doesn’t mean anything, why do you want to get together with me more and more often?” If you do gay stuff around gay people and say it’s not gay, maybe they can tell you that you’re full of crap.

So, context, who is trying to help, and how they do it all matter and contribute to the reasonableness of trying to help someone in their process of self discovery. Of course there are some risks — our attempts to help someone could backfire — but, on the other hand, any help that speeds up the process of self discovery has rewards, both for that person themselves and for those around them. In the example above, if Bill leaves three women wondering about their ability to be attractive to and satisfy men, that has costs and risks, too. And if Bill’s own denial-based claims (e.g., “Gay sex doesn’t count; you’re not gay if you’re married!”) confuses other people about their sexuality and path, that’s a bad thing, too. For trans people, all these issues apply, but there is another: their biological clock is ticking — some aspects of transition are easier the younger you are.

So I would argue that if you you could help someone see their path of self discovery a little better, it could help, and maybe someday they’d thank you for it. Two years ago, I got a slightly unusual opportunity to try.

In this case, my attempt to help wasn’t an in-person conversation. Here, I was writing to internet personality ZJemptv/rmuser (hereafter, ZJ), who had founded both the LGBT subreddit on reddit.com and had a popular YouTube presence with thousands of subscribers and millions of views. Looking back, I’m not sure quite why I wrote, but I think it was mostly that in reading material ZJ had put online, I’d found that ZJ seemed to be playing some kind of game with gender and identity, but there was some mystery as to what exactly this game was. Someone was being fooled in it, but it wasn’t clear who, why, or what the stakes were—they might very well be someone’s life. It was a puzzle, and as I looked at it, I saw ambiguities, contradictions, and parallels. I wanted to tell someone about them, and it seemed rude to tell the whole world, so I wrote directly to ZJ.

It seemed initially like I had wasted my energy. Not, perhaps, unexpected when you write to someone who gets a ton of unsolicited mail from random strangers on the Internet. What had I been thinking? But, three days later, ZJ posted a video Clearing up a few misconceptions which I initially hoped might be some sort of response, but the only purported clarification was “I’m not trans! I’m just not!”, which seemed profoundly unsatisfying given everything I’d said in my message. Still apparently with too much time on my hands, I made a video response, raising some of the questions I’d put in the email message, but it didn’t seem to help much.

I never knew if that email message had ever been read until a few days ago, when I got my thanks for it, if that’s the right word. Zinna Jones had rediscovered my message as she trailed through some old mailboxes after legally changing her name. She has now transitioned, presents full time as female, and is loving the experience of finally growing her own breasts. She’s happier, and I’m happy for her. My message now strikes her as eerily prescient, so much so that it’s almost the moral of equivalent of sending herself a message back through time saying, “Hey, get a clue! You’re a trans woman! Transition already! You know you want to!” and, as such, it provides proof that sending a message back through time doesn’t work, because there are no cheat codes to short circuit the process of self discovery.

Actually though, I never told ZJ to transition, and didn’t expect ZJ to skip any steps in self discovery. I was simply drawing ZJ’s attention to things I’d seen and asking some probing questions. I also wanted to illuminate some of ZJ’s options, so that ZJ’s choices could be informed ones. Today Zinnia says that some of what I said scared her, hitting her in the spot where she was most vulnerable, intensifying her feelings of gender dysphoria. Honestly, I’m unrepentant. Yes, that experience was stressful, and painful, but I still think it helped her in knowing herself and her feelings better.

She says she wouldn’t do what I did, but it’s hard to know. Probably there won’t be another high-profile personality on YouTube doing quite what she did any time soon. But I do know that she likes calling people out when they’re putting stuff out there on the ‘Net that’s blatantly wrong—will she be able to resist? Now perhaps, but in ten or twenty years?

We’ll see, I guess. I can wait.

The Message

This is the message I sent, lightly edited to fix a few typos and remove some personal information about ZJ.

Hi Zinnia,

I’ve enjoyed your videos, blog posts, etc. over the years—I haven’t seen or read every one, but they do tend to strike a chord with me in various ways. I never quite imagined that they’d precipitate a message quite this long (over 3000 words, albeit many of them yours), but there we go…

Let me introduce myself, I’m “sugarandslugs” on reddit—I’m sure you and I have both sometimes commented on the same anti-gay or transphobic threads (on the same side). I also write a very sporadically updated blog at sugarandslugs.wordpress.com, which has about six readers, rather than the two million you have. If you’re ever suitably bored, or bizarrely desperate to figure out what my deal is, you’re more than welcome to check it out.

We have at least one other thing in common: In my past, I freaked people the fuck out because they couldn’t figure out what gender I was, and I took a certain pleasure in it (at least for a while). We’re no doubt plenty different, but I hope that at least I don’t sound like a hater, a spammer, or, for that matter, a stalker. I probably will sound like someone with too much time on their hands, but hey, it’s a weekend, right?

This message was actually inspired by one comment you made on reddit about how you’ve changed over the past few years (i.e., this comment in the thread about physical transformations). I commented there, but somehow it sent me falling down a bit of an Internet rabbit hole, with threads to unpick and leads to follow. Writing this message is my way of extricating myself from said hole. Maybe.

One of the interesting recurring themes in your YouTube channel and your blog is the whole “ZJ vs gender” theme. As you well know, that mostly consists of your having to deal with people who can’t deal with androgyny, genderfuck, etc., and your telling them that you couldn’t really give a shit what some random stranger on the Internet perceives, since that person (usually a guy) is never going to meet you, and if you did meet, your gender ought to be largely irrelevant.

Cool. I feel the same way about sexual orientation. The issue of my sexual preferences are really only relevant if I’m looking for a date, which, as someone in a committed relationship, I most certainly am not.

In replying to your post on reddit, I dug up a video you’d made in July 2010 for International Drag Day and in the latter half, you talked about yourself, describing what you do as drag. You said (transcribed, whee)

Of course, not all drag is so conspicuous. Sometimes it takes a more subdued form incorporating the more commonplace elements of everyday feminine style. If it’s subtle enough, nobody will even notice because there’s nothing that would clue them in. In contrast to the usual drag styles, this can actually be more transgressive of gender roles. It confounds people’s abilities to even recognize that you’re in drag and that you aren’t the gender you’re presenting as.

I’ve actually noticed this happening over the last couple of years. At first people would tell me I looked like a girl. Obviously they thought I wasn’t, or they’d call me a fag, under the assumption that I was a guy. So I decided to change things up a bit. It started out very gradually: putting on makeup, trying on jewelry, new clothes, better hair. And eventually, piece by piece, it evolved into a whole new style. And while I did come up with some looks that are more conventionally glamourous, there was always a more basic fashion underneath, something simple, casual. Surprisingly, this ended up being closer to a genuine feminine style than the excesses of drag. I can tell how effective it’s been because now when people want to insult me they call me a dyke, or call me a man under the assumption that I’m not. Even the haters don’t know for sure any more.

Not to ignore all the positive feedback, of course. There have been plenty of people who say I’m attractive, and they seem to be using the feminine standard of beauty. And it’s really interesting because this seems to be even more of a disassembly of gender roles than the most extravagant varieties of drag. This isn’t just consciously crossing traditional boundaries, it’s almost dissolving those boundaries to the point that people can’t reliably place your gender any more. It’s not utilizing the extremes of gender expression, only the more average elements—the actual feminine styles that are in common use. And in doing so it works to subvert the concept of gender itself, rather than reenforcing it.

And I think this is just another dimension of drag, a different kind of style that’s often overlooked in favor of the more flashy and glamourous varieties. Although, if nobody notices, I suppose that’s kind of the point.

All in all, it’s important to realize that drag isn’t limited to just one form—there’s plenty of ways to do it, including the more understated look. And one of the advantages of this is how accessible it is to the average person. It really doesn’t take a lot of work. If I can do it, almost anyone can. So maybe more people should try doing drag, in their own unique style. You might be surprised at how easy it is. And fun, too!

“Go for it ZJ”, I used to think—you mess with people, subvert the concept of gender itself.

In writing this email message, I dug up a few more self descriptions you’d written, in particular one two months later (September 2010) that matched up pretty well with my perception:

rmuser (aka ZJ or Zinnia Jones) “runs” #lgbtreddit, but doesn’t really do all that much. Moderates /r/lgbt. Most well known for being a gay/genderqueer crossdresser who makes videos about religion and gay rights. Age 21, resides around Chicago, and enjoys activism, making people think, rationality, transhumanism, writing, cooking and pet rats. Aspires to achieve some degree of recognition in life. Gender is a constant source of puzzlement for all who see him. Or is it her?

Cool. You weren’t using the word drag, but it’s the same basic story.

But with your post on reddit about physical transformations, I couldn’t help seeing that you seemed to be on some kind of forward progression. With those photos you admitted to feeling more like yourself as your presentation has changed (to look more feminine). I couldn’t help feeling like I could see a trajectory of self discovery and transformation, and one that is far from over.

And then I found your video from October 2010, “You treat women like that?”—here’s a transcript of the whole thing:

When people think you’re a woman, they’ll treat you like one. And from what I’ve experienced, the way some people treat women is fucking disgraceful. Seriously. It seems like any time a woman dares to be outspoken about anything, there’s always someone there to call her a bitch.

Why? No reason, just because.

You don’t like what she’s saying? She’s a bitch.

You don’t like the fact that she’s saying anything? Call her a bitch.

Who does she think she is, talking about things like that? What a bitch!

Oh, I’m sorry, should we just pipe down and let you do the talking? Should we have let you speak for us instead? I don’t think so. Really, what a great way to never have to listen to someone. Just because they’re a woman.

It’s too easy. Oh, pardon me, I was just being a cunt for a moment there? No, go ahead, let’s hear what you have to say… What’s that? I’m ugly? And you think I’m a dyke? Who gives a fuck! As if there’s anything wrong with that!

What am I, your wallpaper? I am supposed to be your fucking eye candy or something? I don’t remember signing up for that. Since when is it my job to look nice for you? You really think I’m trying to be attractive to you? To you? Who the fuck are you?!? And what makes you think you’re that important? Get a fucking grip.

And thank you for letting me know I have no boobs—I really hadn’t noticed. But since when are they any of your business? I’m sorry, I guess nobody informed me that I have to be a fucking supermodel for you listen to what I’m saying. I’ll get right on that.

Really, do you have any idea how disgusting it is to treat half the world’s population like this? As if all they’re good for is looking pretty for you and if they can’t do that they can just fuck off? Like they only exist for your pleasure rather than as people in their own right?

Did it never occur to you that they might have something more to offer than that? Or do you just not care? It’s honestly terrible to imagine that this is how people might treat your sister, your mother, your grandmother, your friends, and all the women you know. That’s fucking shameful. Really, who the hell do you think you are? People who do this have no goddamn right to look down on women. And how dare you act like you’re fucking better than them. Why is it so hard to treat people like people? Is it too much to ask for a little human decency? Is that really so difficult?

Try showing some respect for a change. Stop acting like the only thing that matters is if we look nice. Stop assuming our only conceivable worth lies in our sexual availability. And don’t you think for a second that we’re only here to make you happy. Women are people. And even if you treat us that badly, it’s people like you that make me want to be a woman — I sure as hell wouldn’t want to be you!

First, I love this rant. I could have made it. I probably have, in some variations over the years.

But what really struck me weren’t the feminism themes, or the cesspool of inane and ignorant comments that got made in response, but what the video revealed about your evolving identity—how you see yourself. You talk about women, and some of the time you say “they”, but other times you say “we” and “us”, including yourself. When I heard that I pointed at my screen and exclaimed “Ha! I knew it!!” (well, honestly, I probably didn’t do either, but I’m telling the story and it makes a better mental image, so let’s go with it).

And at the end, you actually admit that being a woman is actually something that you want to be, albeit offset with the claim that it’s something you’re almost goaded into feeling that way by haters. And maybe I’m projecting, but the anger about the boobs comments seemed, well, telling.

Of course, that’s just one video…

But I got to thinking… Why go by Zinnia now, and not ZJ? You’ve moved from posting as ZJ on emptv.com to posting as Zinnia on zinniajones.com/blog.

And there’s the fact that you’re increasingly active on trans issues, posting on transsexualism-related threads on reddit and video blogging about gender identity. Of course, that can absolutely explained away, given that you are an activist and a general LGBTQ ally (in fact, in my real life, my own trans activism is explained away exactly thus). Plausible deniability is great, isn’t it?

But if your official line on your identity wasn’t capturing the full story, wouldn’t there be evidence earlier, if we looked for it. I’d say there is. Let’s go back to one of your earliest video blogs, “Ain’t I a woman? Well, no.”, where you say

I’ve only been posting on YouTube for a couple of weeks now. […] I really like how easy it’s been to start doing this, and it’s honestly surprising how friendly and welcoming everyone is.

Yes, even the person who felt it was necessary to ask if I’m a boy or a girl. I have a question for them: Are you blind, or just stupid? I don’t mean to be a bitch about this, it’s just I’ve never actually been asked “What gender are you?”

But I honestly can’t say it’s unexpected. This has actually come up before, believe it or not. A lot of the time when telemarketers call, they address me as Ma’am — that’s been going on for as long as I can remember. […]

And yes, a couple of times, people on the Internet have said I look like a woman. But still, nobody has ever actually had to ask. And seriously, if you really think I look like a woman, you should be aware that there are some guys out there who actually do look like women — attractive women even. Believe me, I am not one of them.

But honestly, I’m not bothered about being mistaken for a woman. If the worst thing somebody can say about me is that I look like a woman, I figure I’m doing pretty well, overall. But I am bothered by the implication that this is somehow a bad thing, because it’s not. Women are decent people. Most of them have better hair than I do—I would love it if my hair was like that. You know Ada Lovelace? She was writing programs before computers even existed (in the 1800s) — how awesome is that? Admiral Grace Hopper? She wrote the first compiler for programming languages. You know, women are good people. There is nothing bad about being mistaken for a woman.

But anyway, am I a boy or a girl? The answer is, it really doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter to me, and it shouldn’t matter to you.

With the appropriate hindsight, there seem like some glaring clues:

- In your real life, before you were a youtube sensation, and without really trying at all, there were times when you were perceived as female (although you find it nigh impossible to see how that could happen)

- You say “Believe me, I’m not [someone who looks like an attractive woman]”. You could insert “I wish I did” into that sentence and it wouldn’t be out of place. (If only you from back then could see you now… I bet you’d be pretty surprised at what you’re able to pull off.)

- In talking about how women are decent people (uh, thanks!), you draw on computing pioneers Ada Lovelace and Grace Hopper. I’ll take the leap and infer that you choose them because they’re role models. For you. I wouldn’t be surprised if give a chance to go on, you’d have mentioned Amelia Earhart or Mercy Otis Warren, more uppity subversive women.

- And finally, at the end, with a perfect opportunity do be direct and say that no, you’re a guy, you can’t quite bring yourself to do it. You end saying that gender doesn’t matter. I would claim you say that because that’s the line you can live with, that’s the position on gender that let’s you cope.

Maybe you’re thinking I’m wrong here. Overreaching. Fair enough. And maybe you’re wondering why I should care. Well, I’m not going to win a prize if I’m right about you and where you’re headed. No, it’s about you, and here’s why…

It doesn’t make a huge difference to me or countless others on the Internet where you are headed or how quickly you get there, just what transpires on your path of self discovery, and so forth, except in so far as you increase our enlightenment by explaining your take on things in your usual erudite and thought provoking ways. But all of that stuff really does make a big difference to you.

I don’t envy you the challenges that a process of self discovery can give you to deal with, but I do encourage you to address them than try to defer and hope that somehow that’ll make things better. It won’t.

Referring to passing as a woman, you said “If I can do this, anyone can”, but that’s not actually true. Most men can’t (and, of course, don’t care to either). Even some trans people seem to need to go to deportment lessons to fit in. You’re (un)lucky enough that its quite easy for you, but it’s not going to always be as easy for you as it is now.

You’re 21 now, and you may think that testosterone is done with you, but it’s only just getting started. If you really are a guy, I guess you’ll be cool with the ways your body is going to keep on changing, but if becoming more masculine doesn’t seem like fun times to you, maybe you ought do be doing something about it.

(For things to do, I recommend spironolactone. It’s a pretty safe testosterone-receptor blocker. If you like your progression into a more feminine appearance, it’ll do more great things by letting “the natural you” shine through. And if you like rationalizations, it’s absolutely not hormones—no, sir. Totally justifiable for any self-respecting living-in-the-middle genderqueer person. It’s generic, and cheap. And it’s easier to get a prescription for than full-blown hormones.)

You can tell yourself and the youtube hate machine that you’re messing with people’s preconceived notions, or that what you’re doing is part of a long tradition of drag in gay culture, but do you really believe that, deep down? Does it actually make sense? The number of actual gay guys who do drag where they dress to pass is vanishingly small. Generally speaking, when it comes right down to it, in the main, gay or straight, guys want to be perceived as guys. On the other hand, the number of trans people who told themselves that they were crossing gender lines, but that “it didn’t really mean anything;” well, I think that falls into the common trans themes category.

Staying with trans themes, another common one is “The writing was on the wall for so long, and yet I held back. WTF? Why did it take me so long before I gave in and accepted what was obvious.” It’s something to bear in mind.

Finally, if I am wrong about you, and you really are just a guy who is merely dressing up to break some gender rules, I think you should understand that doing so isn’t inconsequential. Gender presentation isn’t a shirt you put on, it’s part of the food your psyche eats, and we are what we eat. Simone de Beauvoir said “one is not born a woman; one becomes one”, and that is true for me and true for you. If womanhood is not something you want (or at least something you can live with), maybe it’s time to cut your hair and roll out Zarek Jones, fabulous gay man.

But I don’t think that’s true. In my life, I’ve met several people quite a lot like you, insofar as I know you at all. They tasted womanhood, liked it, and (modulo a few bursts of angst and denial along the way) never looked back. They might say to you, “If I can do it, almost anyone can. You might be surprised at how easy it is.”

No matter what, good luck. I’m rooting for you.

Why Sex Differences Don’t Always Measure Up

Every so often, I read an article quoting some claim arising from research on sex differences. Typically, scientists have found some sex difference that they have found to be statistically significant, and the difference is reported with much fanfare and various claims about what this difference means. Unfortunately, a statistically significant difference is not necessarily a useful difference in practice, making many of the ways people interpret the original narrow scientific claim simply wrong.

A naïve perspective on a statistical difference often goes like this: “I heard that girls aren’t as good at spacial rotation as boys are, so I guess that explains why I get lost so easily.” Or, for other differences, someone might say, “Apparently, they’ve found that gay men’s index fingers are longer than straight men’s, so I measured mine and my partner’s. I passed the test, but my partner failed it—I guess he is a bit straight acting.” Or, “Researchers have found that transsexual brains are different from cissexual brains. If only they could have tested me when I was a child, I could have diagnosed back then and been saved a lot of pain.”

The problem here is a fundamental misunderstanding of what statistics tell us. Statistics tell us about properties of samples taken from populations. They don’t necessarily tell us about individuals. To understand why, we’ll look at three sex differences, height, finger length, and brains. Tasty, tasty brains.

Measuring Up the Sexes

Let’s start with height, an “obvious” sex difference. In most human populations, men are noticeably taller than women. For our discussion, we’ll use demographic data from the USA. Men have a median height of 5′ 8.5″ (174 cm), whereas women have a median height of 5′ 3.5″ (162 cm). Thus, we have a tangible sex difference of five inches between the sexes. (I used the median as my “average” here, rather than the mean—see Note 1 at the bottom.)

So, we have a statistic, and it meshes well with our daily observations of life, but what do these numbers actually tell us? Can we use height as a predictor for sex, and, if so, just how good a predictor is it?

To try to answer that question, let’s arbitrarily pick someone from the US population who is 5′ 6.5″ (169 cm) tall, making them 3 inches taller than the median for women, and two inches shorter than the median for men. Naïvely, you might expect that this individual is more likely to be a man than a woman; after all, the person’s height is closer to the male median than the female one. But you’d be wrong. In fact, statistically, it is slightly more likely that the person we have picked is a woman.

It isn’t enough to have a sense of the height of the average man or the average woman. We also need to know something about the distribution of heights in the population. If we measured one million Americans, chosen at random, we would expect to get statistics that look like the ones below:

| Height (cm) | Women | Men | P(Woman) | P(Man) |

| 75–80 | 146 | 100.00% | ||

| 80–85 | 907 | 66 | 93.22% | 6.78% |

| 85–90 | 1,911 | 2,115 | 47.47% | 52.53% |

| 90–95 | 3,915 | 4,708 | 45.40% | 54.60% |

| 95–100 | 4,805 | 4,727 | 50.41% | 49.59% |

| 100–105 | 5,050 | 4,015 | 55.71% | 44.29% |

| 105–110 | 5,303 | 3,941 | 57.37% | 42.63% |

| 110–115 | 4,949 | 5,462 | 47.54% | 52.46% |

| 115–120 | 4,461 | 6,651 | 40.15% | 59.85% |

| 120–125 | 5,347 | 7,371 | 42.04% | 57.96% |

| 125–130 | 5,728 | 6,404 | 47.21% | 52.79% |

| 130–135 | 6,199 | 5,475 | 53.10% | 46.90% |

| 135–140 | 5,265 | 5,056 | 51.01% | 48.99% |

| 140–145 | 6,461 | 7,699 | 45.63% | 54.37% |

| 145–150 | 20,368 | 6,669 | 75.33% | 24.67% |

| 150–155 | 55,291 | 7,245 | 88.41% | 11.59% |

| 155–160 | 99,716 | 10,198 | 90.72% | 9.28% |

| 160–165 | 122,115 | 24,369 | 83.36% | 16.64% |

| 165–170 | 100,480 | 57,832 | 63.47% | 36.53% |

| 170–175 | 41,443 | 94,289 | 30.53% | 69.47% |

| 175–180 | 9,660 | 102,024 | 8.65% | 91.35% |

| 180–185 | 1,521 | 74,355 | 2.00% | 98.00% |

| 185–190 | 54 | 33,282 | 0.16% | 99.84% |

| 190–195 | 12,338 | 100.00% | ||

| 195–200 | 2,212 | 100.00% | ||

| 200–205 | 402 | 100.00% | ||

| Total | 511,095 | 488,905 | 51.11% | 48.89% |

One of the interesting points to note from this data is that our sample has more women than men, because there are more women than men in the US population (men are more likely to die). But it is also the case that men occupy a greater range of heights, so they are necessarily spread more thinly.

If we plotted these counts, they would look like the following:

The graph shows two distributions, one for men and one for women (each roughly following the classic bell-curve shape of a statistical normal distribution). At a little before 5′ 7″ (169.5 cm), they cross—anyone taller than that appears to be statistically more likely to be a man, and anyone shorter is more likely to be a woman. It might seem that we could use this value as a threshold between “female” heights and “male” heights. But there are a lot of people “on the wrong side” of the cut off point. More than 1 in 9 women (11.6%) are taller than 169.5 cm (the shaded pink section of the graph), putting them on the side we might have described as “more likely to be male”, but there are even more men who have “girly” heights: almost exactly one third of men (33.4%) are shorter than 169.5 cm.

So, imagining that there is a height threshold that we could use to reliably partition women from men is false. And our daily experience backs that up. There is a lot of overlap between the range of heights for men and the range of heights for women. Statistically, it may be the case that someone who is 5′ 6″ (167 cm) is more likely to be a woman, but 1 in 3 people of that height are men, which means as a test to sort men and women, a height threshold would be wrong quite often. Of course, in places where the distributions have less overlap, things are more clear cut; for example, only 1 in 10 of people 5′ 3″ (159.5 cm) tall are men, and only 1 in 10 people 5′ 9.5″ (176.5 cm) are women. And there are very few women taller than 6′ 1″ (185 cm).

It’s tempting to imagine we might be able to salvage the simple threshold idea by saying that people taller than 176.5 cm are usually male and a those shorter than 159.5 cm are usually female, and abandoning everyone the middle (more than half of our sample!) as living in a gray area. But even that doesn’t work. Once we get to people shorter than 4′ 9″ (145 cm), there is no reliable gender difference. There are 60,447 women less than 145 cm tall, and 63,690 men, making it pretty much a wash. But because there are more men than women, there are proportionately more particularly short men (13% of all men) than short women (11.8% of all women).

So even though height is a sex difference that is fairly visible in the world, and the difference between the height of men and women is statistically significant, it’s difficult to put this information to good use to make predictions about individuals. If all we know is that men have heights centered around 5′ 8.5″ and women have heights centered 5′ 3.5″, that’s not enough information to make any reasonable predictions at all about individuals, and certainly not enough to use someone’s height to predict whether they are male or female. Even with a better sense of how height is distributed, we can only predict gender with at least 90% accuracy for 34.7% of people, mostly people who are really tall (but also people between 5′ 1″ and 5′ 3″). In other words, even though knowing the statistical distributions for the heights of men and women can tell us something some of the time, for most people, knowing their height is useless for making reliable predictions about their sex.

Furthermore, we have not even begun to consider other factors that influence height, such as race and ethnicity. For example, an average woman from Norway is 5′ 6.5″, but an average man from rural India is only 5′ 3.5″. So, any generalizations we make about height are “all other things being equal”, but in real life, those other factors are not being held constant.

And that was height—what about other sex differences? After all, you’re hardly likely to be considered to have made a major research discovery if you announce that on average men are taller than women. Typically, research on sex differences focuses on more subtle, less obvious differences. These differences are good for headlines, but at least some of the time, the differences that are uncovered, while “statistically significant”, are even less practically significant than height when applied to individuals.

Pull My Finger

With height under our belt, let’s move on to looking at a more subtle sex difference, finger length, specifically the 2D:4D ratio. Here’s what Wikipedia says about it (at the time of writing):

The digit ratio is the ratio of the lengths of different digits or fingers typically measured from the bottom crease where the finger joins the hand to the tip of the finger. It has been suggested by some scientists that the ratio of two digits in particular, the 2nd (index finger) and 4th (ring finger), is affected by exposure to androgens e.g. testosterone while in the uterus and that this 2D:4D ratio can be considered a crude measure for prenatal androgen exposure, with lower 2D:4D ratios pointing to higher androgen exposure. The 2D:4D ratio is calculated by measuring the index finger of the right hand, then the ring finger, and dividing the former by the latter. A longer ring finger will result in a ratio of less than 1, a longer index finger will result in a ratio higher than 1.

The 2D:4D digit ratio is sexually dimorphic: in males, the second digit tends to be shorter than the fourth, and in females the second tends to be the same size or slightly longer than the fourth.

A number of studies have shown a correlation between the 2D:4D digit ratio and various physical and behavioral traits.

It seems to say, then, that we can set a threshold of one for the ratio, with men on one side and women on the other. If you have a ratio of less than one (longer ring finger), you have “boy fingers”, and if you have a ratio of greater than one (longer index finger), you have “girl fingers”. It’s a simple rule that’s easy to remember. But we ought to be suspicious. We had a threshold for height for (169.5 cm), but a full third of men fell into the “girly height” category. And we haven’t been told anything about the average ratios for men and women, or their distribution. At the time of writing, no such information is on Wikipedia about that.

So, let’s dive into a paper on the topic. For convenience I’m going to pick just one paper that has a moderately good sample size, The Visible Hand: Finger Ratio (2D:4D) and Competitive Behavior, by Matthew Pearson and Burkhard C. Schipper. Here’s their data (see Note 2):

| Race | Sex | Count | Average | Std Dev | Min | Max |

| White | Male | 35 | 0.960 | 0.026 | 0.899 | 1.022 |

| Asian | Male | 47 | 0.944 | 0.026 | 0.882 | 1.000 |

| Hispanic | Male | 10 | 0.954 | 0.025 | 0.913 | 1.002 |

| Black | Male | 2 | 0.951 | 0.015 | 0.941 | 0.962 |

| Others | Male | 6 | 0.973 | 0.025 | 0.938 | 0.998 |

| All | Male | 100 | 0.952 | 0.0272 | 0.882 | 1.033 |

| White | Female | 20 | 0.959 | 0.030 | 0.898 | 0.999 |

| Asian | Female | 65 | 0.963 | 0.026 | 0.912 | 1.033 |

| Hispanic | Female | 5 | 0.948 | 0.043 | 0.898 | 0.996 |

| Black | Female | 1 | 0.917 | 0.917 | 0.917 | |

| Others | Female | 7 | 0.978 | 0.034 | 0.942 | 1.033 |

| All | Female | 98 | 0.962 | 0.0293 | 0.898 | 1.033 |

The first intriguing detail is that no group has an average greater than one. Women, in aggregate, do not match our intuition of a “girly“ finger length ratio at all, averaging 0.962. Also, while the paper does claim to have found a statistically significant difference between men and women in general, for white women, they failed to find any significant difference at all, which is just as well, because their white women had more mannish hands than their white male counterparts—oops!

The authors of the paper don’t give us the distribution for their data, but they do give the standard deviation, and so it is reasonable to assume that we can approximate it with a normal (bell-curve) distribution. The graph below shows what the two distributions look like:

As you can see, there is a lot of overlap. If we used finger length as a sex test, it would be right only 56.7% of the time. It’s only better than 75% accurate for people with finger length ratios of 1.02 and above, and only 1.6% of the population are fall into that category. It’s only 90% accurate for people with a finger ratio of 1.06, which is a tiny 0.026% of the population.

Also, while the test can accurately identify a very small number of women, it can never accurately identify men. It is at its most clear-cut at a ratio of 0.89; 3 out 5 people with that ratio (60%) are men.

So while the researchers for this paper did find an actual “statistically significant” difference between the finger ratios of men and women, in practice the difference is not one we can usefully apply to individuals.

Other researchers have examined finger-length ratios of smaller groups, including gays and lesbians and transsexuals. They, too, have found “statistically significant” differences, but we have no reason to expect that they will be any more useful, especially as the sample sizes for these groups are smaller and the differences observed more subtle, as we will see in our final sex difference.

Brains, Bring Me Brains

Brains are a favorite choice of sex-differences researchers, so let’s pick one random study of brains, namely Male-to-Female Transsexuals Have Female Neuron Numbers in a Limbic Nucleus, by Kruijver, et al. Here’s a summary of their results (see Note 3):

| Subjects |

Mean BSTc |

Std Dev | |

| Cissexual Gay Men | 9 | 34.6 | 10.20 | Cissexual Straight Men | 9 | 32.9 | 9.00 |

| Transsexual Women | 6 | 19.6 | 8.08 |

| Cissexual Women | 10 | 19.2 | 7.91 |

A naïve view of this data is that transsexual women’s brains look a lot like cissexual women’s brains, and unlike the brains of cissexual men. We might also naïvely suppose from these results that we could have a “brain femininity” test and use it to detect transsexual women (provided that we found killing them and dissecting their brains to make the measurement to be a good trade-off!).

You might be concerned that someone is making a generalization about the world’s hundreds of thousands of transsexuals (we can estimate at least 350,000 in the USA and Europe alone) from comparing six transsexual brains, but let’s forget the issue of tiny sample sizes for now. Instead, we’ll assume that the average and standard deviation values are accurate, and come from data with a normal distribution.

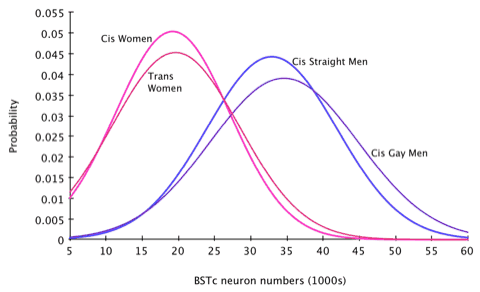

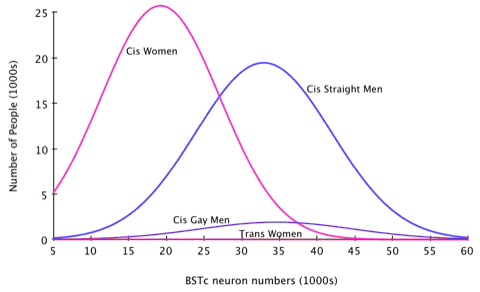

If we examine the distributions, their probabilities look like the following:

Here, we can see that despite the mean BSTc count of the women’s brains being almost half that of men, there is still considerable overlap. If we just compare cissexual men with cissexual women, and say that BSTc counts above 26.5 × 103 are male and those below female, we find that that 23.9% of men have “female” brains, and 17.8% of women have “male” brains.

But the picture changes a lot when you look at the distributions in a context where everyone comes from the same population. As before, we’ll use an imagined sample of one million people from the general population of the USA. In that sample, we’d expect to see about 510,000 cissexual women, 444,000 straight cissexual men, 45,000 cissexual gay men, and a mere 500 transsexual women (plus 500 transsexual men). When we scale the curves proportionately, the bell curve for gay men (about 1 in 10 of the population) drops a good deal, but the curve for transsexual women (about 1 in 1000) flatlines. (I didn’t color the x-axis red; that’s the line for transsexual women.)

Now we can see why a test for transsexualism based on measuring BSTc is not possible (other than that annoying brain-dissection requirement). If we have someone who was born physiologically male who comes to us, survives a brain examination, and appears to have a very “girly” BSTc count in the 14 × 103 range, there will be about 2175 straight cissexual men with a similar value, against only 19 transsexual women. In other words, if you used BSTc measurments to test for transsexualism, you’d only be right on someone with a brain this “girly” a mere 0.76% of the time. Even worse, fewer than 25% of transsexual women’s brains would score this (or more) “girly”—those with less girly brains are even tougher to correctly identify with our putative transsexuality test.

So, even if these researchers have found a statistically significant difference in the brains of transsexual women from their tiny sample of six women, in practice, it is of little use to individual transsexuals.

What Would a Useful Sex Difference Look Like?

If you’re hoping for a sex difference that might be helpful for some kind of test applied to individuals, let me give you some rules of thumb. For gay people (or any group that is about 1 in 10 of the population), you want a difference where there isn’t too much overlap between the two distributions. Since the larger the standard deviation, the greater the overlap, we can set a rule for the maximum standard deviation that will avoid exessive false positives. Find the distance between the average values for men and women (or whatever groups we’re distinguishing between), and divide it by 4. The standard deviation should be no larger than the result. For example, if men average 25 and women average 33, the groups are 8 apart and the maximum workable standard deviation is 2. If it is worse than that, you’ll have excessive false positives (more than about 25%) from opposite-sexed heterosexuals in the tail of their distribution.

For a sex-difference based test for transsexualism (or any group that is about 1 in 1000 of the population), the sex difference needs to have an even smaller standard deviation. To get the rough value you need, divide the distance between the two averages by 7 instead of 4. But the truth is, that would give you two distributions that barely touch at all. Very, very few sex differences are going to be that clear cut. For that reason, you can probably count on there never being a useful and reliable test for transsexualism based on sex differences.

A Test That Works

Despite all that I have said, there is a pretty accurate test for transsexualism, based on sex differences. Simply tell your would-be transsexual about this sex difference, and watch them. If you see them frantically measuring their fingers, or wishing they could scan their brains, they’re probably transsexual. It’s probably not that accurate, but it’s better than we’d do from actually scanning their brains or measuring their fingers.

Notes

- I used the median for the height data because the average and standard deviations are skewed by the long tail at the left of the distribution. The tail is presumably caused by the various disorders that can cause stunted growth.

- In their original paper, Pearson & Schipper seem to come up with a different total, and, more importantly, their standard deviation lacks precision. By using some tricks with the data they do give, I calculated a standard deviation with three digits of precision rather than two.

- The paper presents SEM values (standard error of the mean), rather than standard deviation, but we can convert between the two using the formula stddev = SEM × sqrt(sampleSize).

In Defense of Labels

Every once in a while, I get into a discussion and one of two ideas about “labels” comes up,

- That labels are bad, because each person is special in their own way, and so should not be constrained by some label.

- That people ought to be free to redefine the meaning of labels as they see fit.

Both of these ideas are wrongheaded. Labels exist to facilitate communication; they allow us to fill in a lot of blanks with defaults that can still be overridden by other things we learn about the person. A label does not define someone—it merely provides a useful first-order approximation about some aspect of them.

If someone tells you that I am a liberal/progressive, it tells you a lot about me. It means that I probably won’t be picketing abortion clinics, voting against gay marriage, or demanding tax breaks for billionaires. But it won’t tell you whether I’m an atheist, a liberal christian, or someone who believes in the healing power of crystals—we can easily imagine any of those options. It might make my being a vegetarian a little more likely, but it doesn’t require that I not eat meat.

If a label doesn’t adequately describe me, the right option for me is to either not use it at all, or just add appropriate modifiers to it. For example, I often describe myself as “someone in a same-sex relationship” rather than as “a lesbian”. I think it fits me better. But I don’t mind if other people describe me as a lesbian, and will use it myself on occasion. I’m enough of a lesbian that the correlations outweigh the things that don’t fit (in particular, “lesbian” implies that I am attracted to women in general, rather than in love with one particular woman).

If a label doesn’t fit me perfectly, it certainly doesn’t mean that I need to change myself to fit a stereotype that matches the label. It just means that a bit more explaining is in order before someone knows what my deal is. But that is still less explaining than we’d have to do if we tried to have no labels at all. And it certainly doesn’t mean that I should try to redefine the label so that it either fits me better or so that I can reject it entirely. So, saying, “I’m not a lesbian because I don’t cruise lesbian bars”, or, “I’m not a lesbian because I’m not a Wiccan”, is foolish.

For labels (or any linguistic communication) to work, there has to be a rough consensus about what words mean. Over time, as a culture, we come to interpret words in particular ways, and it is the commonality of our understanding of what words mean that makes communication possible. The meanings can change, and new meanings can be added (so “gay” can go from “happy” to “attracted to the same sex”), but the stability of meaning over reasonable timeframes is what allows us to communicate meanings quickly. If I say that I’ve been crying and need a hug, it’s so much better if you don’t have to ask me what I mean by “crying” and what constitutes a “hug”.

Obviously, the meanings of words aren’t static, and so we’re all free to try to stretch existing words to fit new contexts or develop neologisms to where existing words fail. For example, “heterosexual” and “cissexual” are relatively new terms and both have proved useful alternatives to terms like “normal” that people might have used previously. But coining new words and changing the meanings of existing ones isn’t easy and often fails to get any traction—quite often rightly so.

If a male friend of your comes up to you and says, “I need to tell you, I’m gay”, and then it turns out that what he really meant was that he was happy and didn’t have a care in the world, you might very well tell him that he can take his attempt to redefine “gay” (reclaiming its old meaning) and shove it.

Likewise, if your friend says, “I saw a transhumanist yesterday”, and it turns out that he was actually talking about someone who changed their sex, it’s reasonable to point out that he’s a bit confused about terms. Sometimes people dig in when you do this, and he might argue that people who change their sex are transhumanists. But even if he can somehow make a tenuous argument that this is true, from the perspective of successful communication, he’s wrong—he has used the wrong word and that’s that.

Finally, because labels are part of consensus communication, we don’t get to completely control them. It’s one thing if the label doesn’t match up (e.g., calling me a “religious conservative” would be pretty ludicrous), but if the only problem I have with the label is that it oversimplifies who I am (e.g., that calling me a lesbian doesn’t capture every nuance about my sexuality), maybe the right thing for me to do is get over myself and realize that sometimes other people don’t have the time or inclination to write many words where one or two are sufficient for their needs.

It’s true that when it comes to how people understand me, there are some aspects I think should be more salient than others, and so if I’m introduced to someone new, the order of labels probably does matter, and usually there are many many labels that are frankly irrelevant and don’t come up at all. But these issues are independent of labels themselves, the same issues would apply if we were trying somehow to avoid labels entirely—arguably, the added long-windedness would make the situation worse.

In short, a label does not define me, it describes me in a useful, yet incomplete way. And people who think otherwise, well, I have a label for them…

Maybe False Dichotomies Are Born that Way?

This post is, in some sense, a counterpoint to my Binaries Aren’t Intrinsically Bad post because part of its message is that some binaries are intrinsically bad, but arguably it’s not a counterpoint at all, since those binaries are really two sides of related but different stories.

A false dichotomy is a situation where you lead people to believe that they have to see things in one of two ways, and that those are the only choices. George Bush’s claim that “You’re either with us, or with the terrorists!” is one such example, where any middle ground is missing. But it’s worth realizing that sometimes there isn’t a continuum that connects the two extremes that form the dichotomy. If I say, “Which is it, do you like cats, or are you a communist?”, the problem isn’t that I’ve left you with no middle ground, it’s that the idea of any sort of sensible “middle” between these two options is fundamentally flawed, because these two concepts are orthogonal—each can be true or false independent of the other.

When it comes to identity, whether it is sexual orientation or gender identity, some people feel compelled to wonder, “Are you born that way, or is it a choice?” Most people seem to accept that as a valid question to ask, but I would argue that it’s not—it’s a false dichotomy, and one of the second kind where there isn’t even a middle ground: these are two unrelated propositions, and, worse, the true underlying question, whether we can (or should) change who we are to avoid perturbing other people, is barely addressed at all. To understand why, let’s first ask the same question about some tamer topics and see how it holds up there.

Suppose that at some point growing up I had a bad experience with a particular food, let’s say peppermint liqueur, and now even just the smell of it turns my stomach—to actually drink it would make me gag. It would be absurd to imagine that I have made a conscious choice to gag on peppermint liqueur. Who on earth would want that experience for themselves, with all of its potential for awkward social situations? You’d be a crazy masochist to want that. So it seems reasonable for me to say, “I didn’t choose to be a peppermint liqueur gagger”, but it would be absurd to imagine that I was born to gag on peppermint liqueur (and pretty crazy to go searching for a gene to blame it on).

But just because something wasn’t preordained at birth doesn’t mean it is a thing that I can easily change. Maybe I can hide it a little, but whatever causes me to react in this way seems to be locked-in somehow, outside the reach of my will (and, for the sake of our thought experiment, we’ll suppose that no presently known therapy can change it either, even though that might not be true for some food aversions). Thus, I have a trait that I didn’t actively choose, and I can’t seem to change, even though it isn’t a trait I was born with.

So, “I didn’t choose it and I can’t seem to change it” doesn’t necessarily imply “I was born that way”. What about the other direction, does “I was born that way” imply “I can’t change it”? I would say obviously not—let’s do a simple example for that one…

There are some people who are born with imperfect looking teeth. Sure, they were born that way, but their biology is not their destiny. Orthodontists will happily straighten those teeth for a fee and they’ll be on their way, dental predestiny averted.

The fact that our biology does not always predetermine our fate does not mean that we can always override the cards that biology deals us, or that on those occasions when we can override it, that doing so is necessarily easy enough to be worth our effort. Inborn or acquired, a trait we have may prove to be beyond our capacity to change by effort of will alone.

But the fact that we can’t change a trait we have at will does not mean that the traits that make up our identities are locked into a fixed, immutable state.

It seems reasonable to assume that at least some of the traits that make up our identities are driven by slow-moving, tectonic forces (themselves driven by deep undercurrents), manifesting as subtle gradual movement in a particular direction, with, of course, the potential for an occasional earthshaking jolt. We may be no more able to control these aspects of ourselves than the populations of Australia and Hawaii can stop their land masses from drifting towards each other.

The LGBT community, with its embrace of the “born that way” side of the false “born that way or chose it” dichotomy often seems unsure of how to rationalize the experience of women who embrace lesbian sexuality later in life. To avoid the idea that lesbian women could just choose to turn straight again, they are forced to try to fit the experience of these women into the “born that way” narrative by retconning it, rather than admitting that someone’s identity can evolve, unbidden.

Despite its obvious flaws, the “born that way” narrative remains ascendent. I think the idea of biological predestination lets people feel better. They can say “I was always going to be gay/trans/right handed/Mormon/an asshole/an introvert/whatever, so there’s nothing I could have done.” It’s one of those nice, clean, pat answers people like. Sure, it reduces a complex phenomenon to an easy answer; sure, it’s incoherent; and, as we have seen, the second half doesn’t even necessarily follow from the first; but in my experience, most people generally don’t require consistency or logical correctness from the things they believe; they’re looking for comfort and validation. In a hostile world, they want to be absolved and be told that their present situation is not their fault.

(Actually, that’s oddly dualistic view of things; to say that you and your biology are two separate entities, and that we can lay blame with one rather than the other. It’s almost like a murder trial where the killer asks to be absolved because it wasn’t he who committed the crime, it was his hand.)

In my model, I say that my identity is what it is because of an unfathomably complex tangle of innate proclivities, acquired traits, external forces, and a healthy dollop of random chance, stirred gently by a poorly understood feedback loop. That explanation is probably less satisfying for some, but for me, it makes more sense, and I like the idea that I am, at least in part, responsible for making me the person that I am, even if I don’t always understand how I did it.

With my understanding, it is at least conceivable that had I made different choices, I might have become a quite different person. This view is pretty heretical in gay and trans communities, because it implies that there could be courses of action you might take, or have taken, that might affect your chances of ending up gay or trans.

I agree that this explanation might be more politically awkward, but if that explanation turns out to be the true one, truth should really win out over political expediency. And, really, so what?

This dichotomy exists largely because of people of a conservative/religious persuasion who want to vilify “otherness”. Their mantra is “those people are different from us, but they could chose to conform if they wanted”. You don’t have to say you’re at the mercy of biological predestiny to refute that—it’s sufficient to say that you’re unable to change your identity by any effort of will. But frankly, why should I even be willing to try to change my identity by an effort of will to placate these douchebags? The real response to people who vilify otherness and desire conformity is, “Screw you! It takes all sorts to make a world.”

Binaries Aren’t Intrinsically Bad

There are some people out there who want want to wage a battle against “the gender binary”; in their eyes, dividing people into two groups, men and women, is a mistake. And from their perspective, transsexual people are part of the problem, because they aren’t embracing “the middle” (which is where they believe all gender-variant people belong), but are instead supporting the bad binary bifurcation.

I think there is a logical error here. The existence of things in the middle between two categories doesn’t invalidate the usefulness of (or the existence of) those categories.

To understand why I think this is a flawed way of looking at things, let’s look at another binary categorization: bagels and donuts. Ask people about them, and they’ll tell you various things: bagels are savory and donuts are sweet; bagels are boiled and donuts are fried; bagels are bread and donuts are cake. Yet there are bagels that aren’t boiled, only baked, and donuts that aren’t fried but are baked; there are sweet bagels and savory donuts; and some donuts are made with yeast, which clearly qualifies them as a bread. With so much variance and so much going on in the middle ground breaking the stereotypes of what a bagel or donut should be, shouldn’t we abandon these categories?

I would argue that we shouldn’t abandon categories—bagel and donut are still useful categories even if there is a grey area in between the two. If I tell you I’m serving you a bagel, you’ll be primed with a certain set of expectations, and most of the time those expectations will be useful, even if the particular bagel you get doesn’t quite fit all the aspects of the classic bagel stereotype. It doesn’t make sense to say that people should avoid categorizing toroidal wheat-dough-based foods into these binary categories of bagel and donut, or that if such a food isn’t explicitly labeled as a bagel or a donut, we should avoid prejudging its category, but instead refer to it using the neologism tordo to avoid accidentally calling a sweet bagel a donut. (And people’s heads will spin all the more if activists argue over which neologism to use, is it tordo (toroidal dough-based food), banut, dogel, or something else?)

I’m not opposed to variant bagels and donuts, nor to toroidal dough-based foods that aren’t really bagels or donuts at all, but are their own thing, but being okay with things that exist between and outside existing categories does not require you to support the elimination of those categories.

Activists who advocate for the elimination of binary categories often seem to portray those who use those categories as being too rigid, and themselves as the free thinkers, but to my mind, the real rigidity comes from their viewing categories rigidly. Every bagel doesn’t have to match the stereotype, and we don’t need to say that a donut should embrace its true foodqueer nature as “other” just because it began its life as an unsweetened yeast dough.

Morbid Fascination

I’ve spoken before about how little regard I have for the media’s portrayal of transsexual people, and in particular the bulk of the documentaries that get made about transsexual people. For the most part, the documentary makers prey on vulnerable people who are looking for validation, and they cater to a kind of prurient fascination with the topic of changing sex. Julia Serano does an excellent job deconstructing the tropes of these documentaries in her book Whipping Girl, and so I’ll try not to repeat her too much here. They’re mostly terrible, yet they keep making them and people apparently keep watching, and, yes, I’m one of the viewers.

Mostly the documentaries you’ll find out there follow the “sensitive documentary of human freakishness” tropes you’ll find perfectly parodied by Mitchell and Webb in their sketch The Boy with an Arse for a Face.

Some people have even suggested trans-documentary drinking games. I can imagine some possible rules would be:

- Shows “before” pictures or reveals old name — drink;

- Wrong pronoun used — drink;

- Person embraces strong gender stereotypes (before or after) — drink;

- Person shown getting dressed, applying make up, binding breasts, etc. — drink;

- Person seems to have a largely dysfunctional life — drink;

- Documentary ends with surgery and a vague-but-dubious message of hope — drink rest of bottle.

Yet despite all of this, and the extent to which much of what’s out there in the media frustrates me, I whenever I see that there is documentary about trans people or a movies with trans characters, I usually feel an obligation to watch it.

Back before I transitioned or had even come out, media coverage of transsexualism fascinated me because I hoped it might inform me. A part of me wanted to know everything I could about the mechanics of transition to answer the question whether it was remotely technically feasible in my case. I think what I got out of them was a mix of hope and despair—that it might be possible, but it seemed to be done by people who were nothing at all like me.

One of the earliest documentaries I can remember watching was Paris is Burning, which I saw with my partner of the time in 1990 or 1991. At the time, I was very much in the closet (it would be a few more years before I started dealing with things), and I was starved for information about gender variance. It aired on television, and getting to watch it at all was a challenge—I was afraid of appearing “too interested” in the topic, but I was, of course, very interested. Looking back, it’s not a film that really matches up well with my experience, since it focuses on the drag-ball culture of New York city in the mid-to-late 1980s, but for someone who wasn’t even sure what was possible, it was still quite fascinating. (Of course, I couldn’t really reveal just how fascinated I was at the time—I hardly wanted to out myself—I had to keep my level of interest close to my chest, but I ended up coming very close outing myself anyway. After it was over, my partner made some intolerant remark about the people in the documentary, and I defended them. It was a tense hour or two, and I know that at least one point an accusing finger was pointed at me asking why I should care so much about such people. It was an ugly scene, but one that was quickly forgotten, in part because my behavior actually was fairly consistent with my general stance of cheering for the underdog and supporting oppressed people. Phew!)

I don’t know how many documentaries I got to watch before I found better information sources in Internet communities, but it probably wasn’t many. It was the friends and acquaintances I made on the Internet, who gave me realistic information and the courage to pursue things in the real world, not TV documentaries.

Once I began to deal with things, my relationship to media portrayals changed. For one thing, I didn’t need to be scared about watching them, but I also no longer needed what little useful information they contained. Yet I have continued to watch them anyway, out of a different form of fascination—I can’t help being curious to see how transsexualism is portrayed in the media, and feeling some sort of obligation to watch.

Watching the standard trans-documentary tropes applied to another pitiful person who can’t see the extent to which they are being exploited, is at best something of a chore. But I watch anyway with some resignation, to see how things are being distorted, and what kind of screwed-up person they’ve dredged up this time to be transsexualism’s poster child. Each time I hope that the next documentary will make me cringe a little less than the last, and mostly I’m disappointed.

The most recent documentary I forced myself to watch was, CNN’s Her Name Was Steven, a documentary about Susan Stanton’s transition (although “Steven” gets more screen time than “Susan”). The very title was cringe inducing (although I suppose they weren’t quite at the bottom of the barrel for names—they could have called it “She used to have a penis!”). A better name for the documentary might have been “How not to transition!”, as it tells the story of someone whose life as a public figure meant that they were pretty-much forced to came out as a transsexual at a press conference (before transition) and was unable to escape the ensuing media circus, instead eagerly embracing the spotlight as the media anointed her Florida’s transsexual poster child. Unsurprisingly, things don’t go well in a variety of ways. As a conservative Republican who’d almost certainly benefited greatly from various forms of privilege to become city manager, Susan’s bizarrely transphobic viewpoints hardly endeared her to Florida’s transsexual community. I could say more, but honestly mostly I’d just say it’s another two hours of my time I’ll never get back.

Once in a while, there are a few gems. I mostly enjoyed TransGeneration, which tracked the lives of four trans college students through the 2004–2005 school year. By following students, they avoided the trope of following a sad case who is transitioning as part of a mid-life crisis.

On the movie front, a few nights ago, I chanced on the film Zerophilia, and reading the description which mentioned its being about “a young man who discovers that he has a genetic condition which causes him to change gender,” it had to be watched. As it turned out, it was quite sweet and endearing, if a little silly in places. It’s the old story of boy meets girl, boy becomes girl, etc. At the very least, seeing it made up for sitting through Her Name Was Steven.

Finding My Voice

When I was a child, I was fascinated by vocoders. It was the early 1980s, and vocoders were far too expensive to be affordable, but I so wanted one, because of one thing they claimed to be able to do—a vocoder can turn a male voice into a female one, and that seemed like an amazingly wonderful thing to me at the time. I talked enough about wanting a vocoder that a family member who was into building electronics decided to build me a vocal effects box. He got a kit for a ring modulator and built it for me, but although it could do robot voices, it couldn’t do the one thing I really wanted—it offered no help on the gender front.

So I continued to wish for a vocoder and even dared mention how it could change someone’s vocal range. At that point, I got a lucky break; that same family member who had made me the ring modulator told me something that totally changed my perspective. He told me about a male acquaintance of his who could sing in the range usually considered female just because he had trained his voice—in other words, you didn’t need technology to enhance your vocal range, you just needed practice. Sadly, I no longer remember exactly when I got this revelation, but I do know that it was in my head by sometime in my early teens, and that it was a piece of knowledge that changed my life.

I had always been the kind of child who plays with their voice — from mimicking TV personalities, to beat box sounds to sci-fi effects — so it seemed crazy to me that I hadn’t thought of this approach. Immediately, I began to practice, mostly by singing. Kate Bush, A-ha, The Pet Shop Boys, Erasure, Jimmy Somerville, Eurythmics, Annie Lennox, The Cranberries, and so on. Whenever I wouldn’t be overheard, I sang along trying to match their vocal tone and pitch. Over and over. I was building and maintaining my vocal range in my own informal voice training program. It’s so weird looking back, because at that time, for the most part, I couldn’t really believe that I would ever transition, it seemed like it would be impossible, yet I was planning for it, just in case (or maybe I was just escaping a little, who knows?).

I stole moments for singing whenever I could. Obviously, if I was alone at home, that was a great opportunity, but I found other ones too. In my second year at university, I lived off campus and had a half hour walk to and from campus along lightly traveled streets, and there I would sing knowing that there was no one around me to overhear (except for the occasional cyclist whose silent approach would catch me out and leave me cringing, but not enough to abandon singing while walking alone).

By some point in my early twenties I was willing to use my vocal range in public if the conditions were right. I would sometimes phone a close friend of mine at work and fool her into thinking she was talking to a female secretary from some other office. Officially, it was play, a game of “Can I fool you?”, but at some level for me it was very serious.

But those voices where the voices of characters I was playing. And my attempts to mimic particular singers were just that: singing where I tried to replicate exactly what I heard. Where was I in all this? None of these voices were mine, they were all sounds I could make, but were any of them me?

As I mentioned in my last post, if you read some people’s stories of transition, especially the kind of coverage you see in the media, you hear about their relearning various behaviors, walking, sitting, speaking, and so on. At almost every level, those stories didn’t and don’t resonate with me at all. I think part of it was that I felt that if something is truly part of who you really are, it shouldn’t be forced. In essence, then, although I put in a huge amount of vocal practice to maintain and improve my vocal range, that was all done in the hope that I might naturally come to whatever voice I ended up with—I had no idea what that voice would be.

Unfortunately for you the reader and me the story teller, although how I sound must have changed as I transitioned, I don’t remember clearly what happened, so I can only report the fragments that I do or don’t remember. I don’t ever remember making any dramatic effort to make a serious change in the way I sounded, although I do remember being nervous about how people would perceive me when I first went out presenting as overtly female. I think at some point I was a little surprised that I really didn’t have to try and that I just spoke and sounded, well, like me. I’m sure deep down there is some level of gender normativity policing going on, but it’s at a mostly subconscious level, and I’m pretty sure that whatever policing I have was applied as much (if not more so!) when I was presenting as male. In fact, one few of the things I do clearly recall about my voice around the time I transitioned is what I had to do on the occasions where I needed to return to “(feminine) boy mode” before I was full time; on those occasions I’d “downshift” my voice, pulling in chest resonance. I remember that I found that doing that was the effortful thing, and in fact the whole deal of trying to pretend to be a boy got very draining very quickly, so that period didn’t last long, just a few weeks at most.

I still like to play with my voice. I can do regional accents, different ages, etc. I can also do breathy bedroom voices, girl-trying-to-sound-like-a-boy voices, as well as stranger ones like Yoda, Chewy, and Dr. Claw. Possibly, I might still be capable of doing normal-sounding male voices too, but that is a skill of mine that I haven’t wanted or needed to test in quite a few years. Some part of me has closed the book on that one. But even if I did find and do a voice in that range, it would just be another character I’d be play acting, not me.

I still love singing. I may not win any awards, but it brings me a lot of pleasure. I think years ago, it was a comforting escape, and now, the escape may not be necessary, but some of the comfort remains.

There are a few hangovers from my strange past. It’s hard for me not to clam up if I’m singing and then realize that someone else can hear me, I think partially because of all those years where my singing always had to be secret, and partially because I’m afraid I’ll be told I sound like crap. I’m also fairly ambivalent about recordings of my voice. Sometimes I hate how I sound, and sometimes I’m okay with it or even like it.

In short, my voice, like my body, my attitude, my field of expertise, etc. may not be the most feminine in the world, but it works for me, for the kind of woman I am. I’m glad I have the voice I do, not least because it’s my expression of myself. I’m sure my voice wouldn’t have turned out quite the same way if it hadn’t been for that offhand remark by a family member, who told me, in essence, that my hormonal biology was not my destiny, that with some effort on my part, I could influence the outcome. That’s a mindset that applies to much more than voices, and something that has informed many other aspects of my life.

Life in No Man’s Land

When the media covers transsexual people, there is a lot of interest in the process of transition. Julia Serrano covers their fetishization of transition excellently in her book Whipping Girl. I think we all know the tropes: we open with a picture of Joe as a football player in high school, then cut to Joe at the dressing table, becoming Michelle, putting on heavy makeup, pantyhose, skirt and heels, maybe using a wig, and then trying to “act feminine”. We see “Michelle” learning how to abandon a football-player swagger in favor of a dainty feminine swish; relearning how to talk, ending every breathy sentence with a rising lilt to sound like a vapid valley girl. It’s hardly a surprise that some feminists react to this kind of presentation by thinking that transsexual women are fundamentally phony.

Quite possibly the media’s coverage does represent some people’s experience, but it doesn’t represent how things were for me. I don’t really recall ever trying to change how I did fundamental things like my word choices, the way I move, and so on. I barely changed the way I dress—where I live, plenty of women wear jeans and t-shirts, especially young technical women. If I had to guess, I’d say that I may be a bit butch today, but not so much so that anyone would notice or comment, and before transition, I was probably seen a little feminine for my gender presentation, but again, not really enough for anyone to comment on it (to my face, at least).

Looking back, I think that there are aspects of my transition process strike me as far more interesting than the aspects the media focuses on. Before transition, when I had male gender presentation, although I assumed that I was doing so successfully, it would be fair to that I wasn’t always quite as successful as I thought—apparently my femininity showed through at times in various ways. Apparently, I was always at least a little androgynous. Once I finally began to deal with my gender dysphoria, I started taking spironolactone to block the effects of testosterone while I tried to work out what path I should take, and when I did so, it pushed my body further into the gender no man’s land of androgyny. Physical androgyny allowed me to adopt a gender presentation that offered little in the way of clear gender cues. As a result, sometimes I accidentally passed as female without intending to, but mostly I left people fairly confused. (Actually, according to some sources, apparently I occasionally unwittingly passed as female even before spironolactone, although I’ve never really understood what it was that people could have been seeing.)